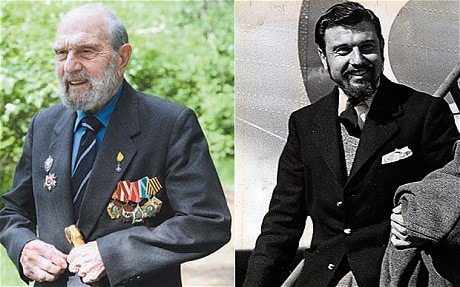

George Blake was perhaps the most successful double agent at the time of The Cold War. Working at the centre of British intelligence, for years he sent invaluable information to the KGB, in particular details of the tunnel the Americans constructed to tap into the Soviet communications across Berlin and the names of over a hundred British agents working there at the time. Blake was captured, escaped and survived and is still living in relative luxury in a dacha on the outskirts of Moscow, but he misses the sun.

So what made George Blake a spy? Was it that he never felt he belonged anywhere? Blake wasn’t even his name. It was Behar, but he was named George after the English King, George V. His father, Albert, had a small company in Holland making heavy duty gloves for dockworkers, but George wasn’t close to his father; they didn’t even speak the same language. George was brought up speaking Dutch; his father spoke English and French. He was also half Jewish; his paternal grandfather had been a carpet dealer in Istanbul, but the family kept that a secret. George was much closer to his mother, who was very religious; he wanted to be a pastor. George always had a strong social conscience.

While George was still at school, Albert’s company failed and then shortly afterwards Albert died. His mother struggled to keep the family in their house by the canal, but his father’s sister had married a rich French merchant and George, his two sisters and their mothers were invited to live with them in their mansion in Cairo. It was there that he completed his education and met his playboy cousin, Henri Curiel, who was the joint leader of the Communist party in Cairo. Curiel was later assassinated in Paris.

He was back at school and staying with his grandmother in Rotterdam when the Nazi’s invaded. He remembered the bombers coming over. His mother was desperate to contact him, but escaped with his two sisters on the last boat to England, the same boat that took the Dutch Royal Family into exile. He came home to find nobody in their apartment and the breakfast things still on the table. He stayed on in Holland for a while, running messages for the Dutch resistance. He enjoyed the excitement of living on the edge. In 1942, he managed to escape through occupied France to Spain and hop on a boat to join his family in England.

In London he grew a beard and was recruited into the Special Intelligence Service. They were impressed by his resourcefulness and need to make a difference. He claimed that he was dropped by parachute in Holland as part of the liberating force, but there was no evidence that was correct. George could be a bit of a fantasist, a Walter Mitty character. So it seemed that George possessed all the credentials to be a double agent: strong social and political convictions but no strong allegiance to any country or any religion, somewhat guarded and secretive, no strong emotional ties, resourceful and independent. He told people he wanted to make a difference in the world.

When war erupted in Korea, he was sent to Seoul and was instructed to go north to Vladivostok and recruit Russian agents who would work for the British. He was in Seoul when communist troops invaded and was imprisoned with other members of western legations. It was while he was a prisoner in Korea that he witnessed the American bombing of Korean villages and decided that he was on the wrong side. Together with the other prisoners, he was escorted on the long march through the mountains to the north. He seized the opportunity to escape but was recaptured. It is probable that he made contact with officers from the KGB at around that time and was recruited as a communist agent.

After 2 years in prison in Korea, Blake was released and sent back to England as a hero, seemingly none the worse for his experience. Impressed by his work in the Far East, he joined MI6. One of his first tasks was to take the minutes for the meeting setting out plans to build a tunnel to tap into the Soviet secret communications channel across Berlin. He printed the document out and handed it to his minder on the top deck of a London bus. The Russians did not react; keeping the identity of such a valuable double agent was too important to them. So they kept their communications open and allowed Blake, now in Berlin, to continue sending his reports on to Britain in return for information from him. He handed over the names of at least a hundred British agents and much more strategic information over the course of the next few years. It was while George was on his next assignment in Lebanon that MI6 grew suspicious of his role in betraying the existence of their tunnel.

Brought back to England for interrogation, he admitted to spying for the KGB and was sentenced to a very harsh 42 years of imprisonment on various counts of treason. While serving time in Wormwood Scrubs, he was a model prisoner and was allowed certain privileges, such as access to the library. It was there he met the Irishman, Sean Bourke, who was doing five years for being connected with a bomb incident. Bourke was impressed by Blake’s courage and convictions and decided to help him escape using a hacksaw and a crude rope ladder and the assistance of some local helpers from the CND. Blake injured himself falling from the wall, but was whisked away to a safe house, where he was patched up by a doctor, the girl friend of one of the conspirators. It was touch and go; there was a massive search for him. He was nearly discovered when the wife of the owner of the apartment told her therapist that she had a spy in her flat. The therapist, however, thought she was delusional and ignored it. Hiding under the seat of a camper van, Blake escaped through Europe and was deposited at the Russian border, where he walked to the guard house and asked to speak to a member of the KGB.

Later in Moscow, he invited Bourke to join him for a holiday in his luxurious, KGB apartment in the centre of the city, no doubt wishing to recruit him. Once there, Bourke found he was trapped. He stayed for a year and a half but was eventually allowed to return to Ireland. The British Government applied for extradition, but the Irish government refused. So Bourke stayed in Dublin and, in between drinking sprees, was able to complete and publish his book, ‘Springing George Blake ‘. He died in 1982, his life cut short by alcoholism.

Simon Gray’s play, ‘Cell Mates’, covers the time from when Blake and Bourke met in the library of Wormwood Scrubs to when Bourke was allowed to return to Ireland. It covers the trajectory of their relationship from Bourke’s idealisation of Blake in the beginning to his disillusion, a course accompanied by his increasing alcoholism. ‘Cell Mates’ is a play about trust and duplicity that questions what drove Blake to be a spy.

There is something detached, almost autistic, about George Blake. He never acknowledged that he did anything wrong. He was convinced that Russian communism was the practical means whereby the Kingdom of God would be built on earth. He regarded Russia as his spiritual home. More committed to ‘the cause’ than people and a narcissistic desire to make a difference, Blake advised his wife, who had also worked for MI6 and by whom he had three children, to divorce him.

Blake still lives in the leafy outskirts of Moscow in the green-painted, wooden dacha, donated to him by a grateful state. He is 95 and seemingly in good health. In 2007, he was awarded another medal by Vladamir Putin for his services to Russia. He has married again and has another son. His second wife still looks after him. Blake has no regrets over what he did. He had no particular loyalty to Britain, but he is disappointed by the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and does not like Putin, though he keeps that a secret from the Russians.

Simon Gray’s play is as enigmatic as the spy, himself. We don’t really get any insights about the relationship between Bourke and Blake. Were they gay? Probably not; Blake was married twice. Did Blake trick Bourke into staying in Moscow with him, only to arrange for him to leave when he realised how unreliable he was? Was Bourke’s life ever in danger? It seems that Blake was too self centred to feel any lasting attachment to another person and any guilt, but has created a myth that he can live with.

He reminds me of Julian Assange, who continues to live in the Ecuadorian Embassy, protesting his right to do what he did, while the world has largely forgotten about him. A recent report said that the Ecuadorian officials were complaining about his personal hygeine. Wikileaks, it seems, has become Whiffyleaks!

Stephen Fry was originally cast to play Blake and Rik Myall was cast as Bourke when ‘Cell Mates’ first opened in the West End in 1995, but the production had mixed reviews and was panned after Fry dramatically left because of depression. This is the first revival since that disastrous opening. Should they have bothered? Probably not. It seems to me that the back story of George Blake is much more interesting than the play.

Cell Mates played at The Hampstead Theatre until January 20th. It was directed by Edward Hall with Geoffrey Streathfield as Blake and Emmet Byrne as Bourke.The

Leave a comment